by Noah Senthil

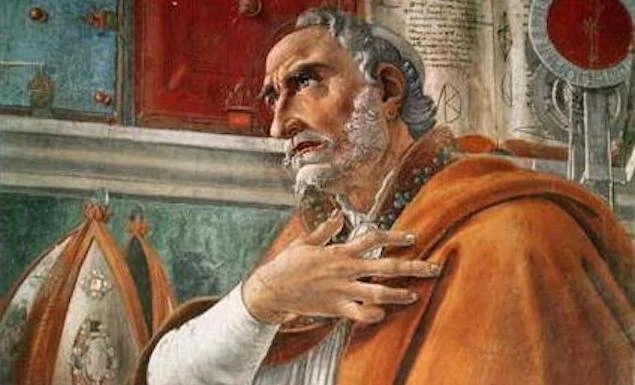

It could be argued that Augustine of Hippo’s experimental, yet masterful work On the Trinity (Latin: De Trinitate) has been more influential than any other in trinitarian theology. The first time I encountered the book, I carelessly and hastily read Augustine’s introduction (Book 1, Ch. 1). Anticipating the depths of the trinitarian dogma that I was about to discover, I neglected the rich wisdom that was already being poured out by this preeminent church father.

The second time I read it, I wrote in the margins, “I’ve never read an introduction like this before.” Most books, whether ancient or modern, have a preface or introduction, which usually includes an attempt to give an outline of the chapters or to set up prevalent forthcoming themes, but while Augustine does those things to some degree, he also establishes a sacred relationship with his readers. He describes the relationship between himself and the readers as a covenant, one intended to keep them walking along Charity Street together, neither moving ahead nor trailing behind without each other. It is worth quoting at length:

“Accordingly, dear reader, whenever you are as certain about something as I am go forward with me; whenever you stick equally fast seek with me; whenever you notice that you have gone wrong come back to me; or that I have, call me back to you. In this way let us set out along Charity Street together, making for him of whom it is said, Seek his face always (Ps. 105:4). This covenant, both prudent and pious, I would wish to enter into in the sight of the Lord our God with all who read what I write, and with respect to all my writings, especially such as these where we are seeking the unity of the three, of Father and Son and Holy Spirit. For nowhere else is a mistake more dangerous, or the search more laborious, or discovery more advantageous.”[1]

Augustine continues on by explaining the stipulations of this covenant, which are especially important when we encounter roadblocks on Charity Street, that is, one partner being impeded by the other. Although Augustine is writing directly for the readers of De Trinitate, we’ve already seen his desire for this type of relationship to be fostered “with respect to all [his] writings.”

Personally, I’ve found his thoughts on charitable reading and writing to be worth carrying over into all other theological works, and even reading and writing in general, regardless of the topic. For this reason, I’ve attempted to distill his thoughts into three principles:

1. Charity in the Absence of Clarity

Numerous factors possess potential for lack of clarity or miscommunication between an author and their readers. It is difficult to place blame, because it could be the fault of either party. Therefore, Augustine makes room for both possibilities: “Whoever reads this and says, ‘This is not well sad, because I do not understand it,’ is criticizing my statement, not the faith; and perhaps it could have been said more clearly—though no one has ever expressed himself well enough to be understood by everybody on everything.”

He is careful to point out that absence of clarity from the author does not mean the argument is invalid, regardless of which side the impediment is on. Moreover, because no one has the ability to communicate perfectly (i.e. being understood by everybody on everything), Augustine suggests reading others who have written on the topic—those who may be able to bring about greater clarity. He suggests, “Let him lay my book aside (or throw it away if he prefers) and spend his time and effort on the ones he does understand.” However, this does not mean that the author never should have written in the first place: “Not everything, after all, that is written by anybody comes into the hands of everybody,” and perhaps someone will never come across those more “intelligible writings” but will have happened upon his work. He concludes, “This is why it is useful to have several books written by several authors, even on the same subjects, differing in style though not in faith, so that the matter itself may reach as many as possible, some in this way others in that.” If, however, someone is unable to understand any of these works, then they should probably study harder before critiquing anybody else.

2. Charity in Response to Disagreement

There are other cases where there may be no misunderstanding but, rather, informed disagreement. For Augustine, this is not an occasion to forsake the covenant and depart from Charity Street, but simply another place where charity is most necessary: “On the other hand, if anyone reads this work and says, ‘I understand what is being said, but it is not true,’ he is at liberty to affirm his own conviction as much as he likes and refute mine if he can.” Augustine does not say this begrudgingly but with a joyful undertone. If the reader disagrees and refutes his view with charity, Augustine would be happy to be disproven for the sake of truth: “If he succeeds in doing so charitably and truthfully, and also takes the trouble to let me know (if I am still alive), then that will be the choicest plum that could fall to me from these labors of mine.”

Although we must remember the specific context in which he is writing—that is, in regards to his ongoing meditations on the Trinity—there is much to learn from his general posture. Namely, that he, as the author, has come ready to learn, and so he is not asking the reader to do anything he is not already doing himself. Furthermore, Augustine is “trusting in God’s mercy” to preserve him in the truths he is certain of, and to reveal to him anything he is incorrect about through “hidden inspirations and reminders,” the Scriptures, and fellow Christian brothers.

3. Charity in the Case of Unfaithful Followers

The first principle addressed those readers who are aware of an absence of clarity, and indeed, are frustrated by it. The third principle concerns those who are unaware of their own lack of clarity, wrongfully assuming that they know the author’s true meaning, and consequently, criticizing or praising the author for erroneous reasons.

Concerning these, Augustine says, “Nobody, I trust, will think it fair to blame me for the mistake of such people if they stray off the path into some falsehood in their effort to follow and their failure to keep up with me, while I am perforce picking my way through dark and difficult places.” Augustine further illustrates this idea: “After all, no one would dream of blaming the sacred authors of God’s own books for the immense variety there is of heretical errors, though all the heretics try to defend their false and misleading opinions from those very Scriptures.” Augustine’s point is that we should refrain from judging if our critique is merely of the abuses and misinterpretations, rather than the author and his actual work.

An implicit lesson to learn from this principle is the importance of reading primary sources before criticizing someone; reading or hearing from a secondary source is not satisfactory, regardless of whether they are a follower or a critic. However, it is not only the reader who needs to rein in his criticism and practice charity, but the author as well. For even in cases of abuse or misinterpretation, Augustine feels bound by the rule of charity. So, even when someone thinks he means something that he never meant, and one person approves of the falsehood while another disapproves, he prefers “to be censured by the censurer of falsehood than to receive its praisers’ praises.” In this statement, Augustine practiced charity by applauding his censurer or critic. Even though the critic is wrong to blame him for someone else’s misinterpretation, they are right to disagree and criticize the falsehood, which is something worth commending and being grateful for.

___

[1] Saint Augustine, The Trinity, trans. by Edmund Hill, Second Edition (Hyde Park, NY: New City 1 Press, 2015). All quotations are taken from Book I, Chapter I, pages 68-69.