by Noah Senthil

The widely debated topic of the Eternal Subordination of the Son (ESS) has emerged at the forefront of recent trinitarian controversies. Some prefer to speak of ‘Eternal Functional Subordination’ (EFS) or ‘Eternal Relations of Authority and Submission’ (ERAS), and while there are nuances along this spectrum, the underlying proposition remains the same. Namely, although the Father and Son and are co-equal and share one essence, the Son is eternally subject to the Father, functionally and/or by way of eternal relationship.

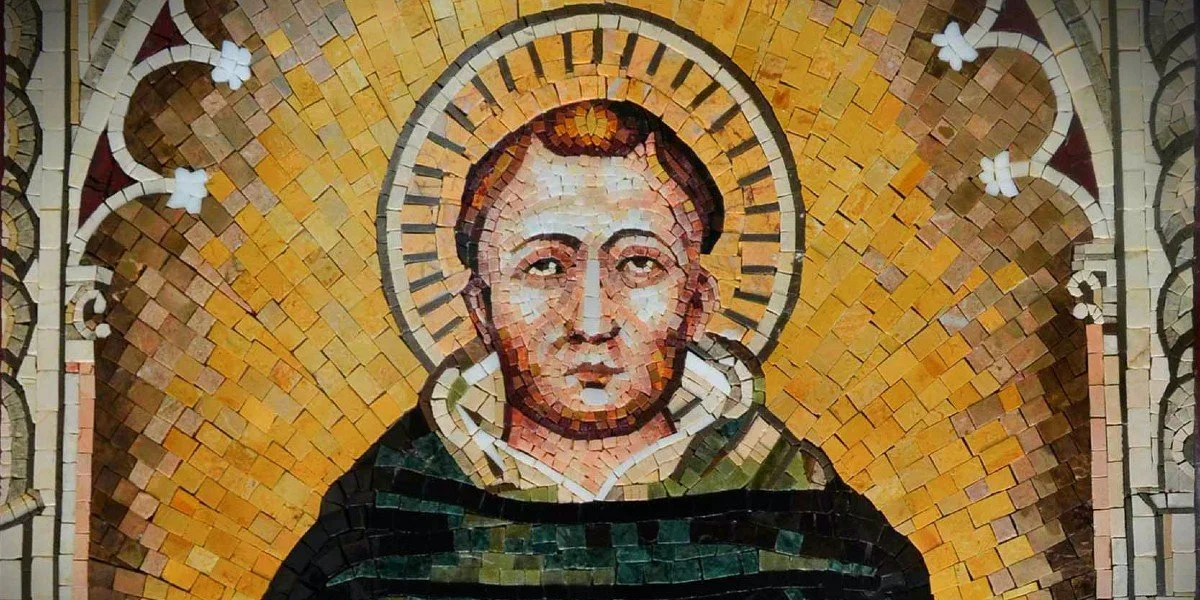

Whenever new (or old) trinitarian debates arise it is imminently important to retrieve historic, trinitarian doctrine. Augustine’s De Trinitate has rightly been utilized as a comprehensive standard of orthodox teaching on the Trinity. However, there is another monumental theologian who has much to say about the relations between the eternal persons of God. Thomas Aquinas, who is thoroughly Augustinian in his own right, proposes a myriad of questions in his magnum opus, the Summa Theologica; all questions are answered using the following methodology:

• A number of objections are initially given, opposed to what Thomas will argue afterwards.

• An appeal to a higher authority is given to offer an ‘on the contrary’ claim to the previous objections.

• A response is given to the initial question.

• Each objection is sequentially given a reply that aligns with the argument in Thomas’s response.

Part III, Question 20 of the Summa is immediately relevant to this controversy. There are two articles, including two interrelated questions, under the heading Christ’s Subjection to the Father. The first, “Whether we may say that Christ is subject to the Father?” The second, “Whether Christ is subject to himself?” Before we attempt to apply Thomas’s work to this contemporary debate, I will summarize and explain his work on the topic, while also allowing him to speak for himself where needed.

Whether We May Say that Christ Is Subject to the Father?

Thomas offers a nuanced, clarified response to this question (and the preceding objections) by appealing to two figures of authority. First, Christ himself, who says, “The Father is greater than I.” Second, Augustine in De Trinitate: “It is not without reason that the Scripture mentions both, that the Son is equal to the Father and the Father greater than the Son, for the first is said on account of the form of God, and the second on account of the form of a servant, without any confusion.” Thomas bases the crux of his argument on Augustine’s aforementioned contrast, which is found in Philippians 2:6-7: “[Jesus Christ] who, though he was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied himself, by taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men.” His conclusion is that the less is subject to the greater; therefore, in the form of a servant Christ is subject to the Father.[1]

He lists three reasons why human nature (the form of a servant) is necessarily subject to God, and how Christ (in the form of a servant) is subject in all three ways.

1. While divine nature is the very essence of goodness, a human nature has only a participation in the divine goodness; Christ said that only God is good (Matt. 19:17), thereby confessing that in his human nature he did not attain to the height of divine goodness.

2. Because of God’s power every human nature is subject to his divine ordinances; everything that befell Christ occurred by divine appointment.

3. Human nature is especially subject to God when it obeys God’s commands by its own will; Christ said of himself, “I do always the things that please him” (John 8:29), and he subjected himself to the Father in obedience to the point of death on a cross (Phil. 2:8).[2]

Thomas helpfully clarifies his view in a reply to an objection:

“As we are not to understand that Christ is a creature simply, but only in His human nature, whether this qualification be added or not, as stated above (Q. 16, A. 8), so also we are to understand that Christ is subject to the Father not simply but in His human nature, even if this qualification be not added; and yet it is better to add this qualification in order to avoid the error of Arius, who held the Son to be less than the Father.”[3]

Whether Christ Is Subject to Himself?

Again, Thomas grounds his argument in the trinitarian thought of his favorite theologian, Augustine, by quoting De Trinitate: “Truth shows in this way (i.e., whereby the Father is greater than Christ in human nature) that the Son is less than Himself.” Thomas builds on his answer to Whether we may say that Christ is subject to the Father?, arguing that if Christ is subject to the Father in his human nature, then he must be subject to himself in human nature:

“Further, as he [Augustine] argues (De Trin. i, 7), the form of a servant was so taken by the Son of God that the form of God was not lost. But because of the form of God, which is common to the Father and the Son, the Father is greater than the Son in human nature. Therefore the Son is greater than Himself in human nature. Further, Christ in His human nature is the servant of God the Father, according to John 20:17: I ascend to My Father and to your Father, to My God and your God. Now whoever is the servant of the Father is the servant of the Son; otherwise not everything that belongs to the Father would belong to the Son. Therefore Christ is His own servant and is subject to Himself.”[4]

In typical Thomistic fashion, he is careful to precisely define what he does not mean alongside what he does mean. Thomas does not mean that there are two persons in Christ, one who is ruling and another who is serving (that would be the heresy of Nestorian). He is arguing that there are two natures in Christ, which is the historic Christian position clarified at the Council of Ephesus (AD 431), and of these two natures in the one person of Christ, one is ruling and one is serving:

“Second, it may be understood of the diversity of natures in the one person or hypostasis. And thus we may say that in one of them, in which He agrees with the Father, He presides and rules together with the Father; and in the other nature, in which He agrees with us, He is subject and serves, and in this sense Augustine says that the Son is less than Himself.”[5]

Clearly, precise theological thought is necessary here, and therefore, equivalently precise theological language is necessary. What is directly correlates to what we may say. We may say of “Christ” or of the “Son” whatever is true of the Person, because whatever is said of the Person is eternally true. However, what pertains to him only in his human nature is to be attributed with a qualification. We may say that Christ is simply “greatest,” “Lord,” or “Ruler,” because this is eternally true of the Person, whereas to be “less,” “servant” or “subject” is to be attributed with the qualification “in his human nature,” because this was not eternally true of the Person.[6]

Whether Christ Is Eternally Subject to the Father?

Recently, some evangelical scholars have argued that the Son is eternally subordinate (subject) to the Father.[7] Proponents of this view are careful to emphasize that the three persons of the Trinity are co-equal and co-eternal, therefore, the Son is not ontologically subordinate but relationally subordinate. The Son’s submission to the Father is a marker of their eternal relationship or roles—it is why the Son is not the Father and the Father is not the Son—and the incarnational submission of the Son is only a reflection of this eternal reality.

As Protestants we believe that the Bible is the supreme authority on the matter, but that does not mean that tradition is devoid of authority altogether; to use a relevant analogy, the Great Tradition is eternally subordinate to the word of God but the voice of the Church still has a role. While I would argue that Thomas is wrong on a number of theological points, he has biblical, theological, and historical reasons for correcting us as well. This current controversy is an example of an area where retrieving Thomas’s theology might help us. He has been clear, precise, and comprehensive.

Summary

Christ is subject to the Father in the form of a servant—in his human nature, not in the form of God—in his divine nature. Furthermore, the form of God is common to both the Father and the Son; they share one divine essence. Therefore, if Christ is subject to the form of God in the Father, then he is subject to the form of God in himself. Christ is subject to himself in human nature, because the form of a servant is less than the form of God. It cannot be said of the Person, that is, “Christ” or the “Son,” that he is simply subject to the Father, because he is only subject in his human nature. It is true that the Son is subject or subordinate to the Father, but it is not eternally true because the divine Person was not always united to a human nature.

___

[1] Thomas Aquinas, Summa theologiae, rev. ed., trans. Father Laurence Shapcote of the English Dominican Province (1864-1947), III, q. 20, a. 1. aquinas.cc

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Aquinas, ST, III, q. 20, a. 2.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] See, for example, Wayne Grudem, Systematic Theology: An Introduction to Biblical Doctrine, (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1994), 249; Bruce Ware, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit: Relationships, Roles, and Relevance (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2005), 79.